(ENG) Beyond the Sampans: The 5 Secret Histories of Hong Kong's Aberdeen Harbour

Aberdeen Harbour is far more than a scenic backdrop. As these five stories show, it is a living archive of identity, commerce, faith, and conflict. From a 300-year struggle for human rights to the modern tension between industry and luxury, its waters hold the memories of a city in constant flux.

Listen attentively to the fascinating stories of tourism history.

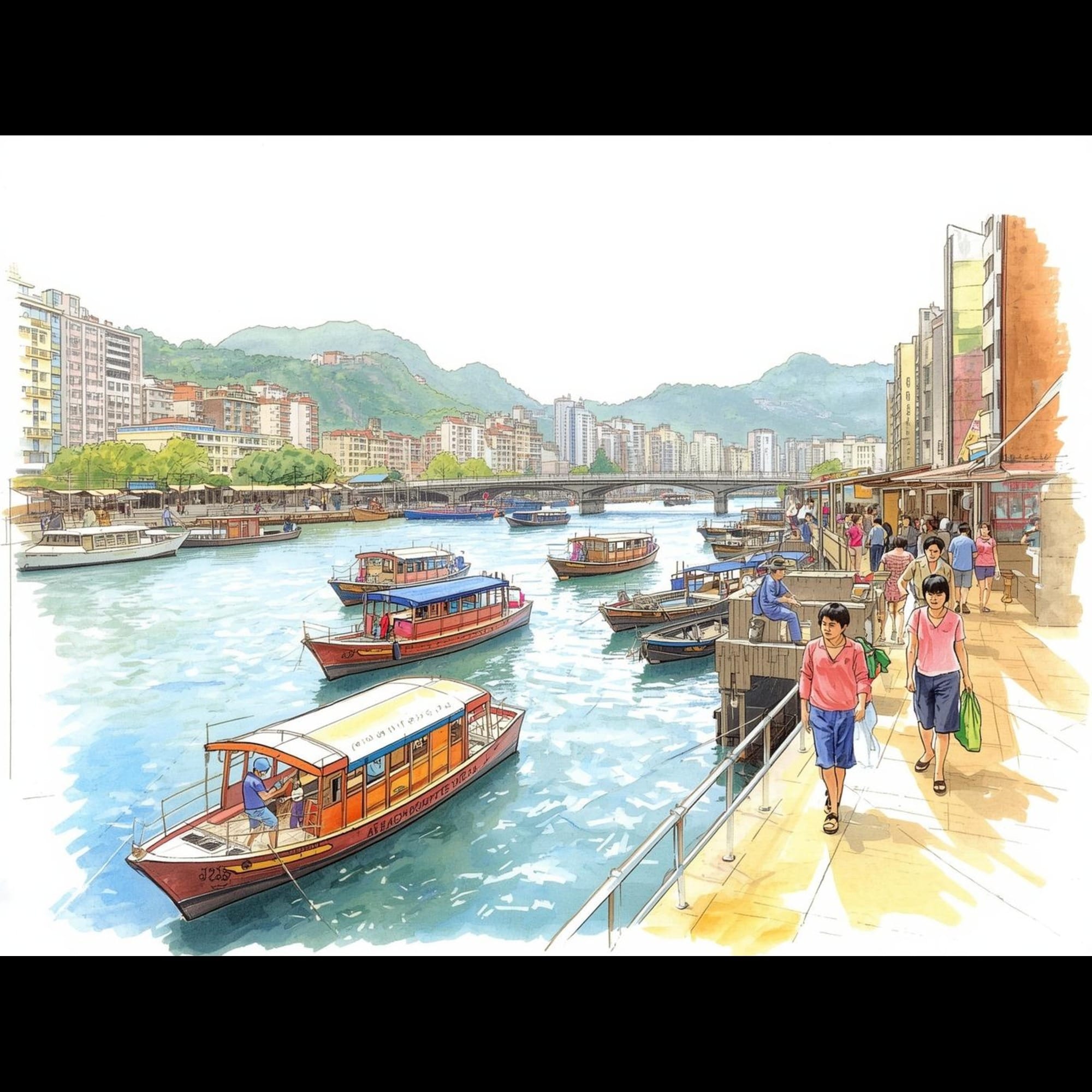

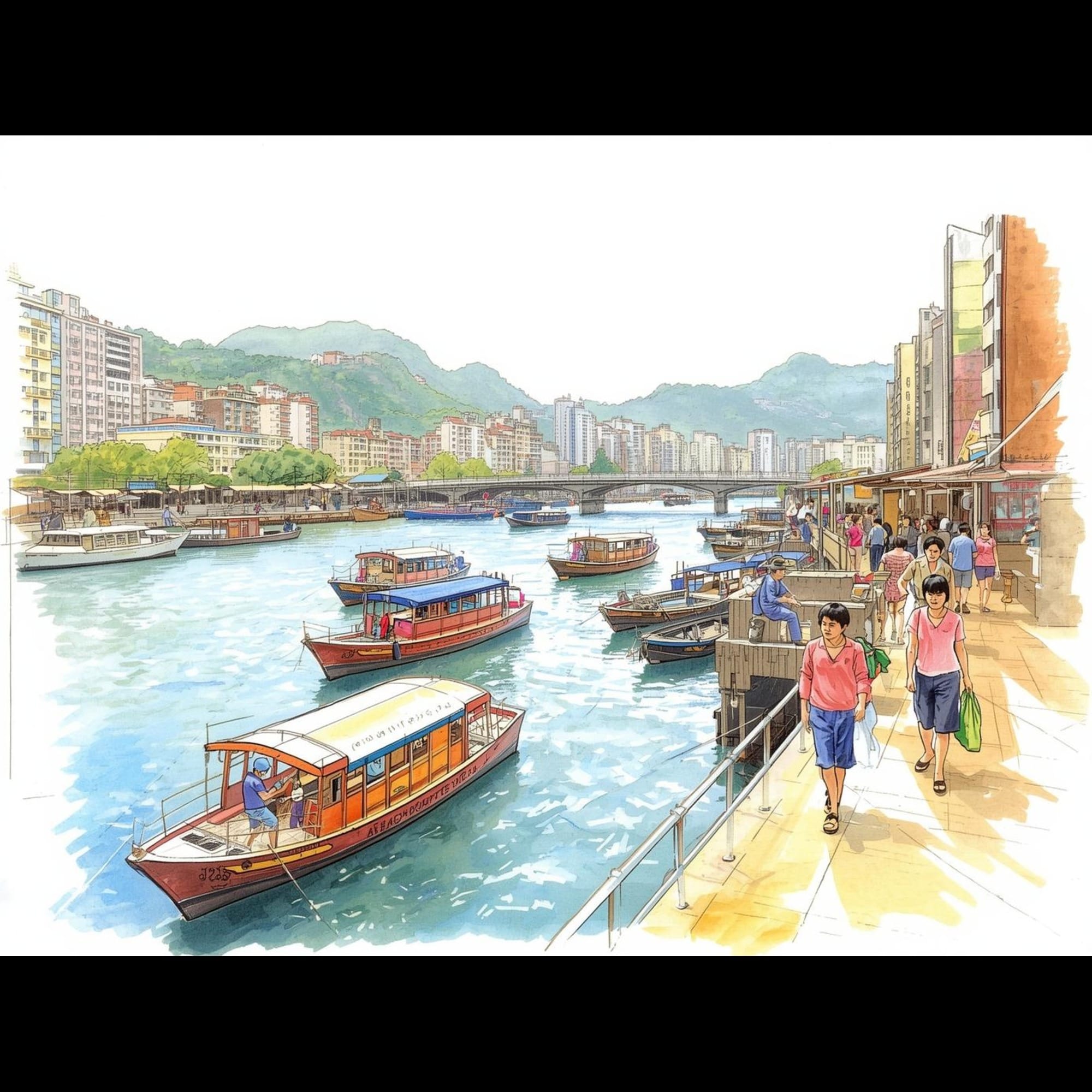

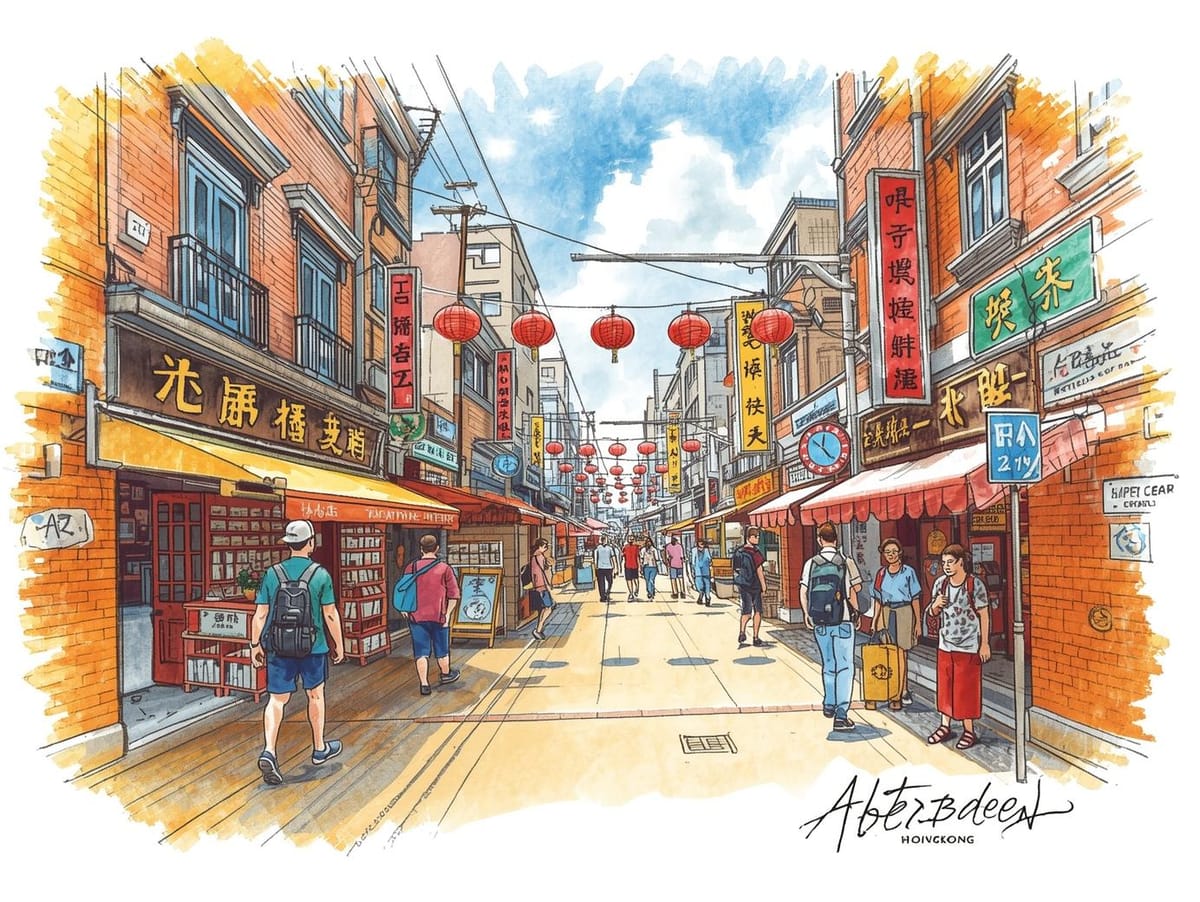

Mention Aberdeen Harbour, and a familiar image surfaces: colourful sampans gliding past colossal floating restaurants, tourists capturing the perfect snapshot of a timeless fishing village. This vibrant, bustling scene is an iconic part of Hong Kong's identity, a living postcard that seems to tell a simple story of tradition and seafood.

But this picturesque facade conceals a history far deeper and more turbulent. The calm waters of the typhoon shelter are a living archive, holding centuries of struggle, innovation, and conflict. Beneath the modern gloss of luxury yachts and tourist attractions lies the soul of a community shaped by imperial decrees, pirate legends, divine protectors, and the relentless currents of modernity.

This is not just another travel guide. Our purpose is to uncover five profound stories that reveal the true character of Aberdeen and its neighbouring island, Ap Lei Chau. From the legal liberation of an "untouchable" caste to the modern-day battle for space between steel trawlers and superyachts, these hidden histories offer a rare glimpse into the heart of the "Fragrant Harbour."

From "Untouchables" to Citizens – A 300-Year Struggle for Land

A pivotal moment in the history of Aberdeen’s fishing community occurred not on the water, but in an imperial court nearly 2,000 kilometres away. For centuries, the Tanka people (蜑民), who lived their entire lives on boats, were officially classified as a "lowly caste" (賤民) during the Qing Dynasty. Subjected to profound social discrimination, they were denied the same rights as land-dwellers.

In 1729, the Yongzheng Emperor issued a groundbreaking edict that legally granted the Tanka equal status as "good people," an act of liberation that should have changed everything.

"The Tanka households are originally good people, and there is no reason to despise or abandon them... they pay the fish tax and are one with the common people." [2]

However, legal equality did not translate to immediate social change. The emperor’s decree came with a crucial condition: Tanka people could move ashore only if they were wealthy enough to build their own houses. For a community living a subsistence existence, this economic barrier was insurmountable. As a result, most remained on the water for another two centuries, their new legal status a distant promise.

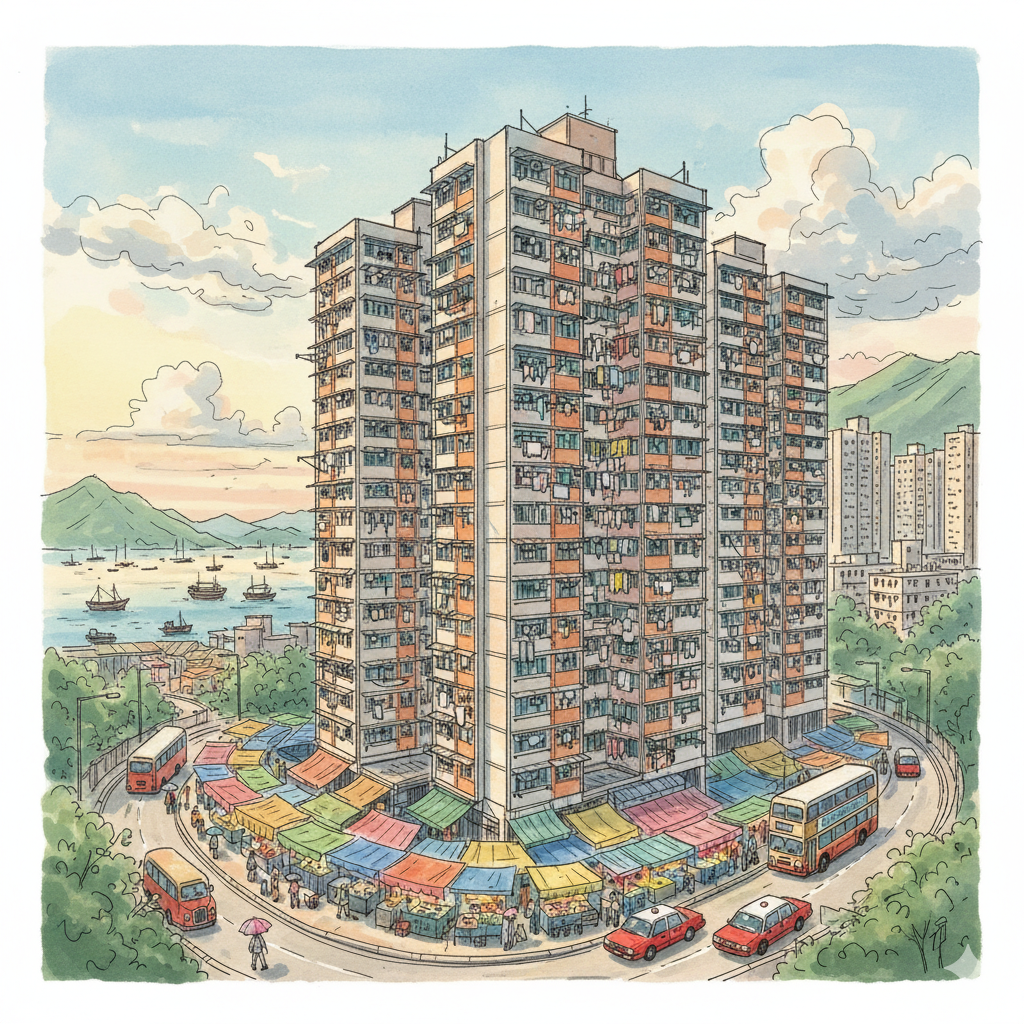

The final chapter of this long journey was not a triumphant march ashore, but a "passive landing." In the post-war era, catastrophic fires, like the one that ravaged the crowded boats at Yung Shue Au, forced government intervention. The physical embodiment of this transition is Yue Kwong Chuen (漁光邨), one of the first public housing estates built to resettle the displaced Tanka. It stands today as a quiet monument to a 300-year struggle, marking a forced migration from boat to building and the final, complex step in their quest for true citizenship.

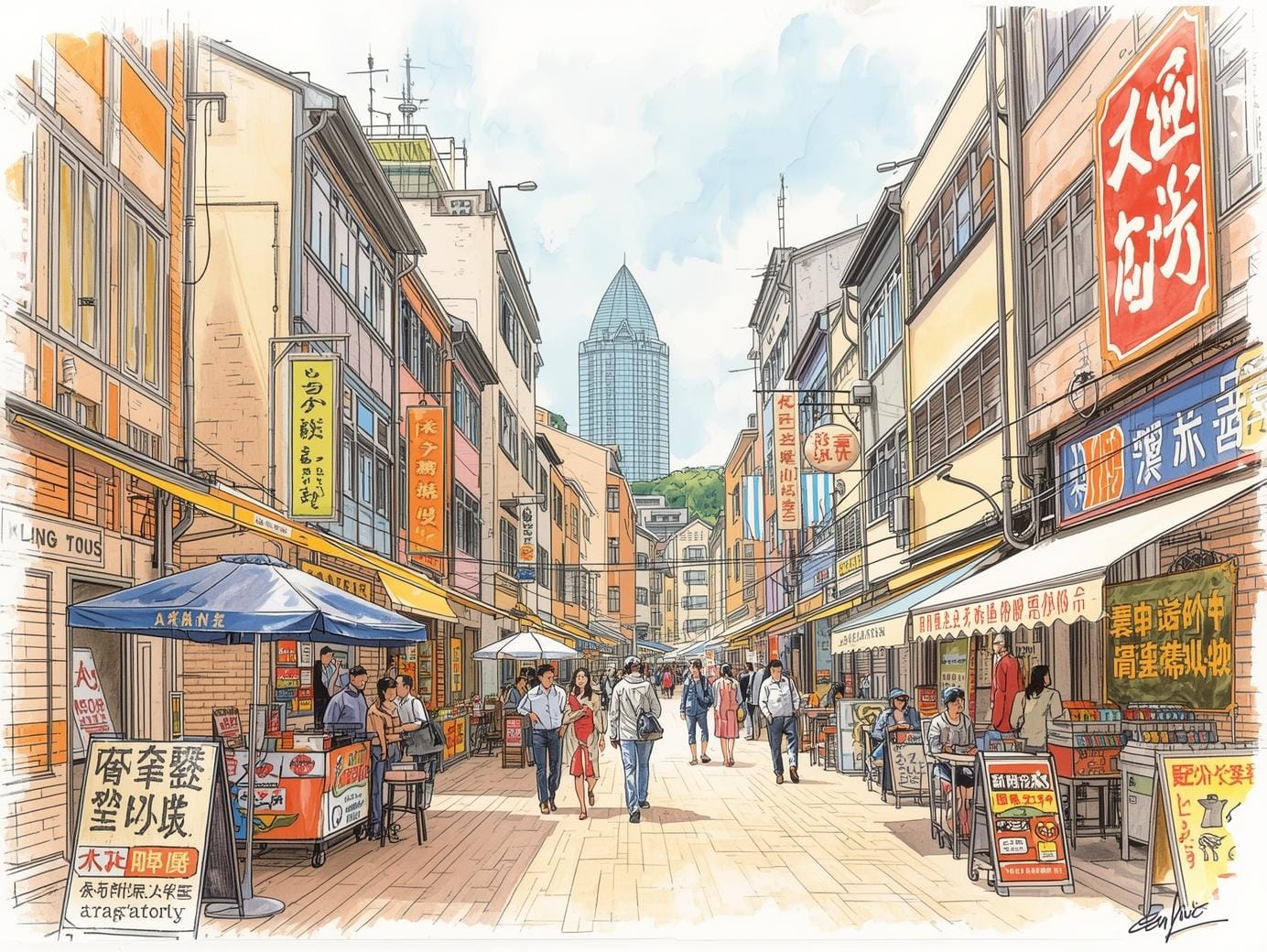

The Floating City – A Lost World of Commerce and Craft

Before high-rises dominated the skyline, the Aberdeen typhoon shelter was a self-sufficient “floating city,” an aquatic ecosystem so complex and vibrant it was often compared to a living "Qingming Scroll." This lost world was a marvel of organization, where specialized boats provided every imaginable service to the water-dwelling community.

There were humble dwelling boats where families lived, alongside a bustling fleet of mobile businesses. Grocery boats sold dry goods, firewood boats provided fuel, and the famous noodle boats (粉艇) served the iconic dish of boat noodles (艇仔粉). Even social life and entertainment had their place, with raucous banquet boats (歌塘船) for celebrations and cheerful ice cream boats (雪糕艇) navigating the waterways to delight children.

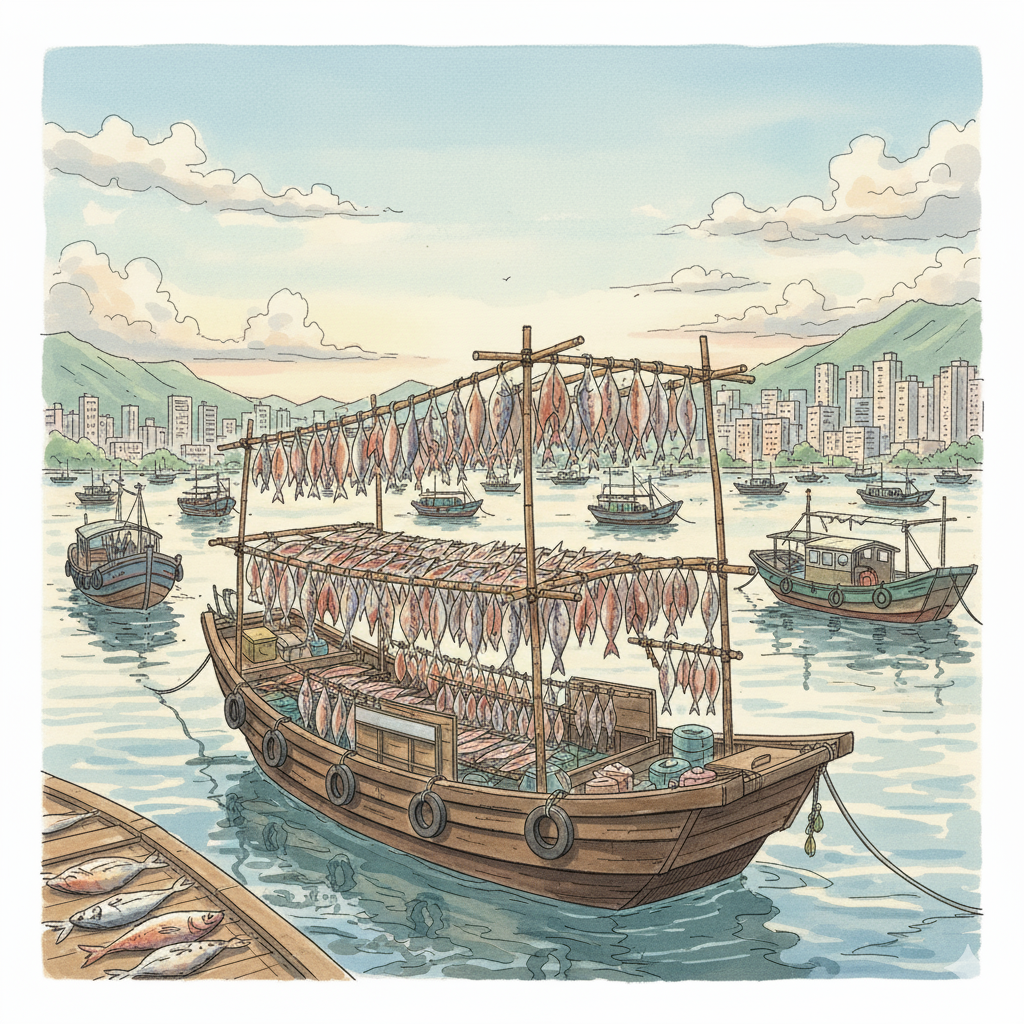

Among the most unique vessels were the sgaa-gaa syun (曬家船). These were engineless hulks with no bow or stern, moored in a fixed position under a special license, serving as both homes and workshops. Their decks were once covered with drying seafood, producing the famous "Kowloon dried squid" (九龍吊片). Today, this traditional craft has all but vanished. It is believed that only "one" of these boats is still actively used for drying fish, a true living relic of a bygone era.

For the modern explorer, two hidden gems from this floating city remain. The first is the challenge of spotting that last active sgaa-gaa syun from a sampan. The second is tasting a bowl of authentic boat noodles, the last, delicious edible link to this once-thriving floating marketplace.

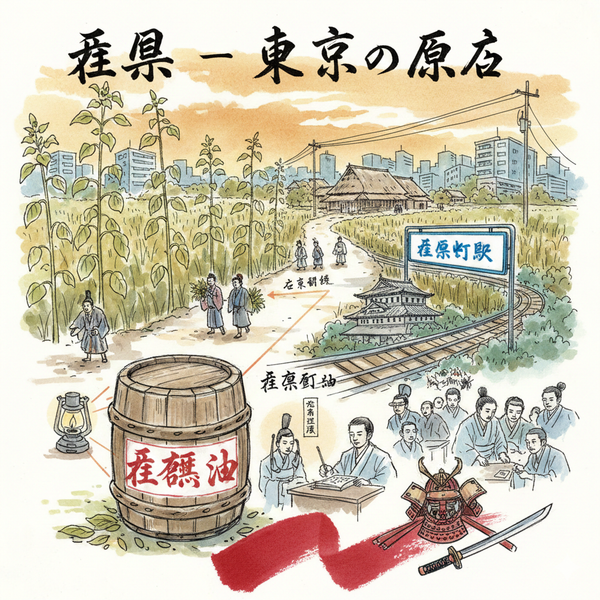

Fragrant Harbour, Pirate's Lair – The Dual Identity of the Coastline

Hong Kong’s elegant name, "Fragrant Harbour" (香江), finds its roots right here on this coastline. The name implies a connection to the historic agarwood trade in the New Territories, its scent carried on the fresh water of a stream that was a vital resource for international sailors in the age of sail.

The hidden gem at the heart of this legend is Waterfall Bay (瀑布灣), a cove just west of Aberdeen where a cascade of fresh water once flowed directly into the sea. This life-giving source, which allowed ships to replenish their supplies, gave the entire region its famous name.

Yet, this same life-sustaining coastline had a darker, more dangerous identity. In the early 19th century, the area’s hidden coves, rocky shores, and island barriers made it an ideal hideout for Cheung Po Tsai (張保仔), one of South China’s most notorious pirates. His fleet used the natural geography of Aberdeen and Ap Lei Chau as a supply base and sanctuary from imperial authorities. Here, in the reflection on the water, one sees the fascinating duality of the landscape—simultaneously a source of life-giving "Fragrance" for legitimate traders and a den of lawlessness for pirates. The legendary sea caves on Ap Lei Chau, still rumoured to hold pirate treasure, are a tantalizing reminder of this duality.

Gods of the Sea – An Unseen Division of Labour

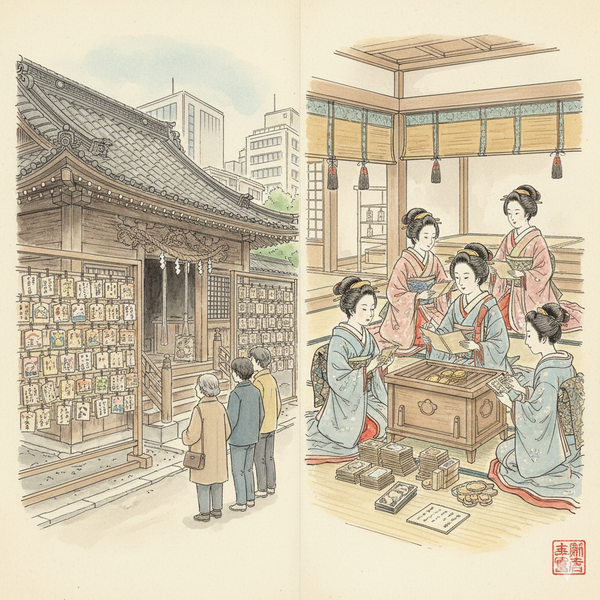

The spiritual life of the Tanka people was as practical and sophisticated as their life on the water. While Mazu (Tin Hau) is widely known as the goddess of the sea, the fishermen of Ap Lei Chau held a special reverence for another deity: Hung Shing (洪聖). A Tang dynasty official famed for his expertise in geography and weather prediction, Hung Shing was seen as a key protector.

In the local belief system, there was a clever division of divine labour. Mazu was the goddess who protected sailors on long-distance ocean voyages, but Hung Shing was the god of the "inshore waters" and local weather. This distinction is a sophisticated cultural mapping of rational risk assessment. For the local community, which mostly engaged in coastal fishing, sudden changes in local weather were the greatest threat. Hung Shing was the specialist they turned to for immediate protection against immediate dangers.

This faith also reflected the economic realities of the past. The physically demanding fishing industry created a high demand for male labour, so families once prayed to Hung Shing for sons—a tradition that has now faded. The historic Ap Lei Chau Hung Shing Temple is the primary hidden gem for understanding this practical faith. For an unforgettable cultural experience, visit during the Hung Shing Festival, held on the 13th day of the second lunar month, to witness the community's enduring respect for its divine protector.

Steel Trawlers vs. Superyachts – The Modern Battle for the Harbour

It is a common mistake to view Hong Kong’s fishing industry as a romantic, "sunset industry." In reality, it has evolved into a high-capital, modern enterprise. Today’s fleet includes massive steel-hulled trawlers, high-tech vessels that can cost up to 30 million HKD per pair. This is a world away from the small wooden boats of the past.

This industrial reality creates a stark visual contrast in the harbour today. Moored near these powerful working vessels are hundreds of gleaming luxury yachts, particularly concentrated near the local yacht club. This juxtaposition is a microcosm of modern Hong Kong—a clash of class, culture, and the use of public space, which can lead to friction between the local fishing community and new boat owners. As the previous generation of fishermen often lamented:

"There are more yachts than fishing boats now."

The hidden gem here is not a place, but an experience: a "social observation tour" taken from the promenade. The view of the yacht club and the trawler mooring area tells a powerful story of Hong Kong's ongoing economic transformation. But this story has a poignant postscript. The traditional shipyards that service these vessels now face a crisis of succession, with "no one to inherit" the craft. This raises the ancient paradox of the Ship of Theseus: as the old parts—and the old masters—are replaced, is the harbour’s soul still the same?

The Harbour's Soul

Aberdeen Harbour is far more than a scenic backdrop. As these five stories show, it is a living archive of identity, commerce, faith, and conflict. From a 300-year struggle for human rights to the modern tension between industry and luxury, its waters hold the memories of a city in constant flux.

In transforming this working harbour into a "destination," a critical question of ethics emerges. We must remain vigilant and "avoid letting the fishing community become a background for curious onlookers." The true hidden gem is not the picturesque decay of old boats, but the living knowledge of the fishermen, their resilient community, and their ongoing story. To visit Aberdeen is to witness a profound dialogue between past and present, a negotiation that will define the soul of this harbour for generations to come.

Listen attentively to the fascinating stories of tourism history.